BEHIND THE SCREENS: A DIFFERENT TYPE OF DIGITALISATION IS POSSIBLE

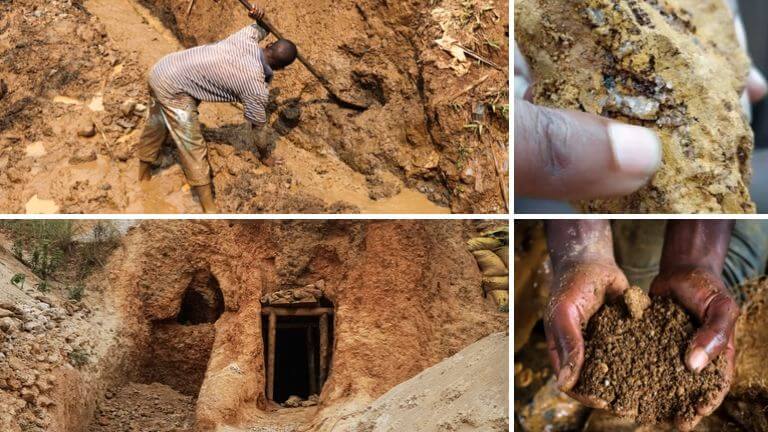

The negative consequences of mining natural raw materials in the East of Congo are well documented. When the connection between conflict minerals and the millions of victims of the big African war were formally recorded by the United Nations, legal measures were taken; through the international conference of the Region of the Great Lakes and through the American Dodd-Frank law that forces manufacturers to give transparency into the supply chain. The European guideline will come into force in 2021. But what really is the effect of these guidelines?

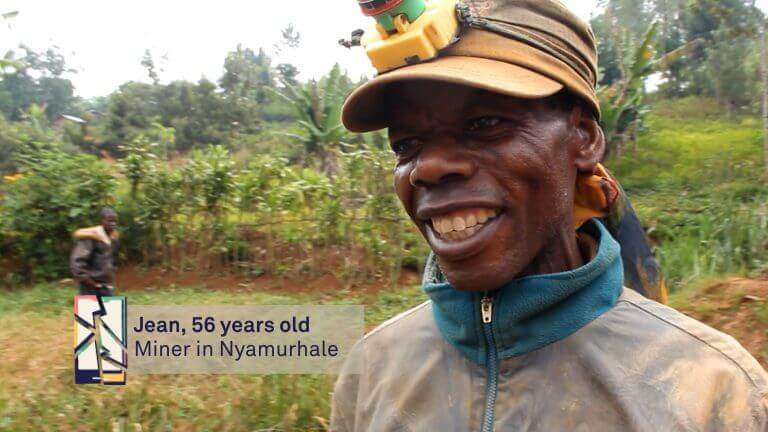

The certificates – the guarantee that the mineral raw materials are not controlled by armed groups and that no child labor nor labor by pregnant women was used – are based on the traceability of the chain “from mine to pocket”. The mechanisms that are currently being used have their limits, especially as not all states apply them in the same way. And although more and more mining sites are now certified, there are still missing links in the chain, which means that mineral raw materials from non-certified sites can still end up in the supply chains. Those are raw materials that may therefore be related to human rights violations. These measures also have perverse effects. The armed groups may have fewer connections with the mines, but they continue to have a strong grip on the natural resources (forestry, fishing, etc.) and on the limited income of the local population (through roadblocks, looting, etc.).

But if the promises of the new Congolese mining code are kept and the artisanal mining sector succeeds in organizing and formalizing itself better, then the profits of the mining sector could be better distributed through real cooperatives and redistribution mechanisms of the planned taxes. For the benefit of the community. Good governance will be the key. And the introduction of a lasting peace in the region will be THE priority which all forces involved must agree on.